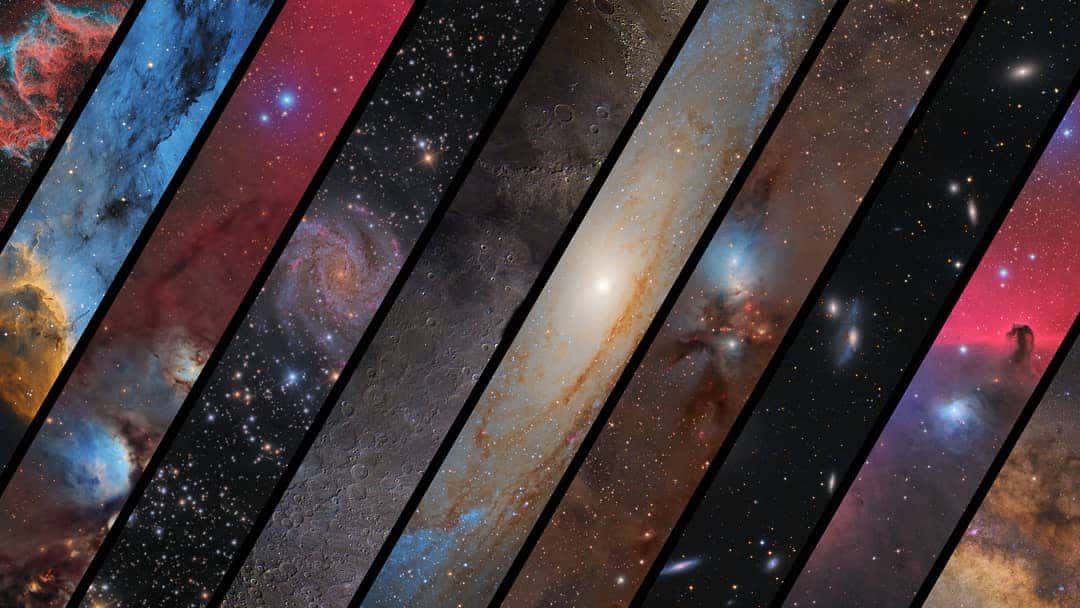

Astrophotographers: Interviews & Case Studies

Here we present interviews and case studies from some of the best astrophotographers in the world.

Check out any of the articles below to get an overview of how your favorite astrophotographer goes about their art.

Deep Sky Astrophotography

Nightscape & Deep Sky Astrophotography

Nightscape Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography

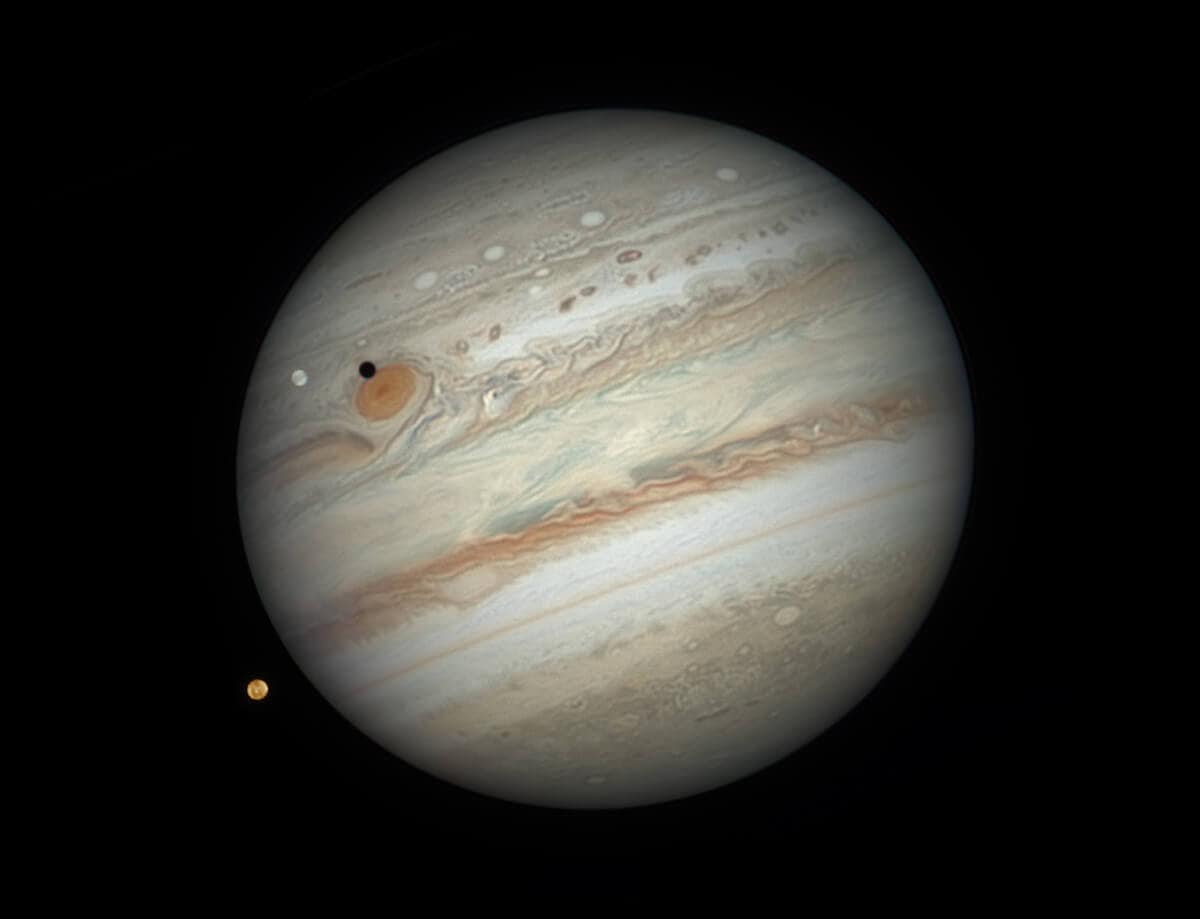

Deep Sky & Planetary Astrophotography

Collaborative Deep Sky Astrophotography

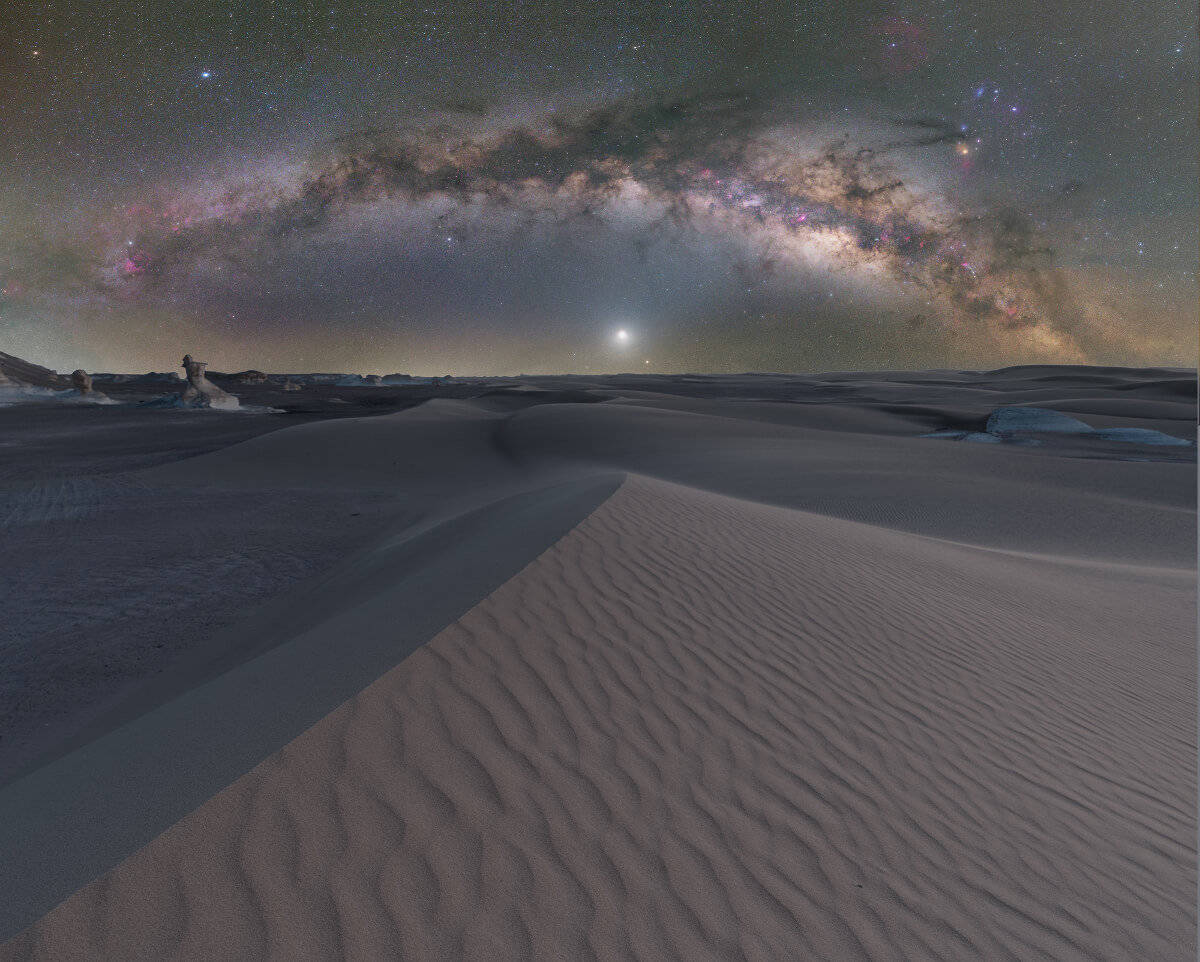

Landscape Astrophotography in the Atacama Desert

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape and Deep Sky Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography in the Himalayas

Landscape Astrophotography in Australia

Using Telescope Live for Deep Sky Imaging

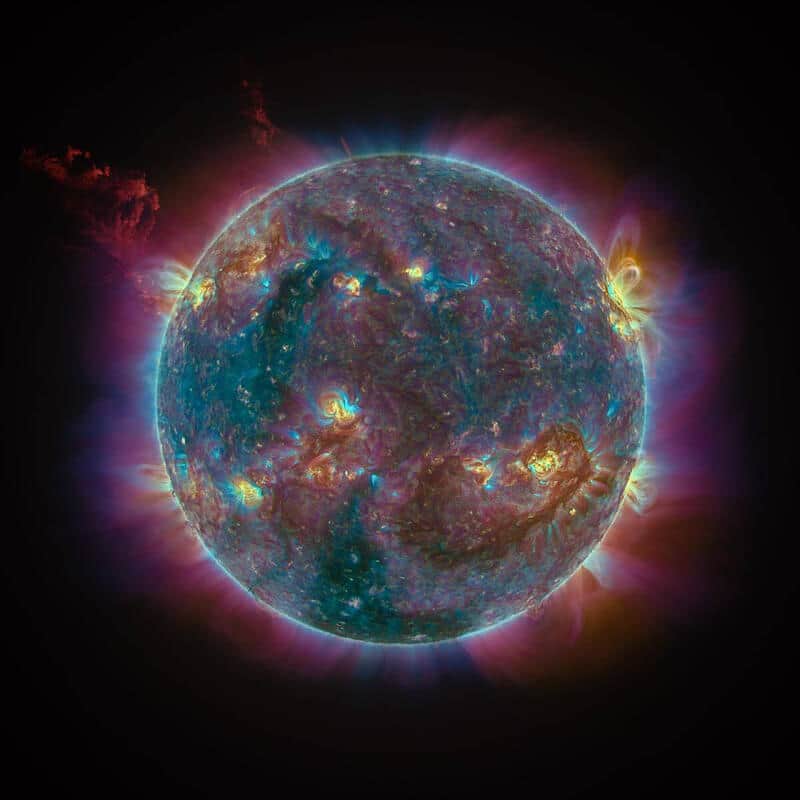

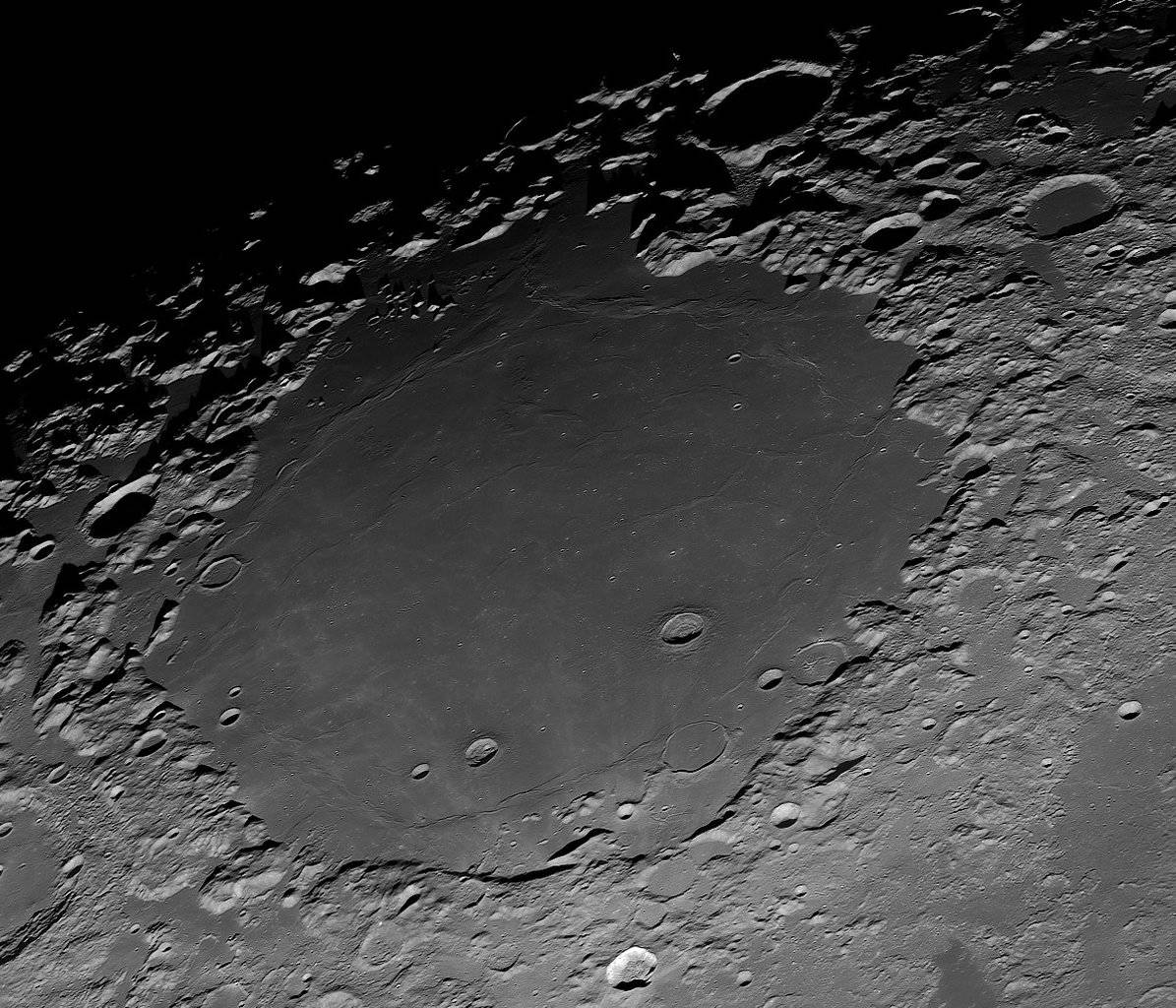

Solar, Lunar, Deep Sky and Landscape Astrophotography

Deep Sky and Landscape Astrophotography

Amazing Travel Astrophotography

Landscape astrophotography and rare night-sky phenomena

Landscape, Lunar and Solar Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography in the Mountains

Star Trails and Landscape Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Remote Deep Sky Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography

Aurora and Milky Way Photography

Landscape/Deep Sky/Planetary Astrophotography

Nightscapes and Deep Sky Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography using Public Data

Landscape Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography

Deep Sky and Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape and Deep Sky Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Deep Sky Astrophotography

Landscape Astrophotography

Aurorae & Landscape Astrophotography

Remote Observatory Profile

Best Astrophotographers

Thank you to all the amazing photographers featured here for giving their time to share how they go about their art!

Let us know in the comments below if there is anyone you think we should add to this piece or contact us directly if you ‘d like to be featured.

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles