In this interview, we talk to Sergio Díaz Ruiz who is an award-winning expert at processing astrophotography images using data from public sources.

Whilst he does capture his own astrophotography data, he talks below about why processing data captured from other sources to produce something unique is a great option.

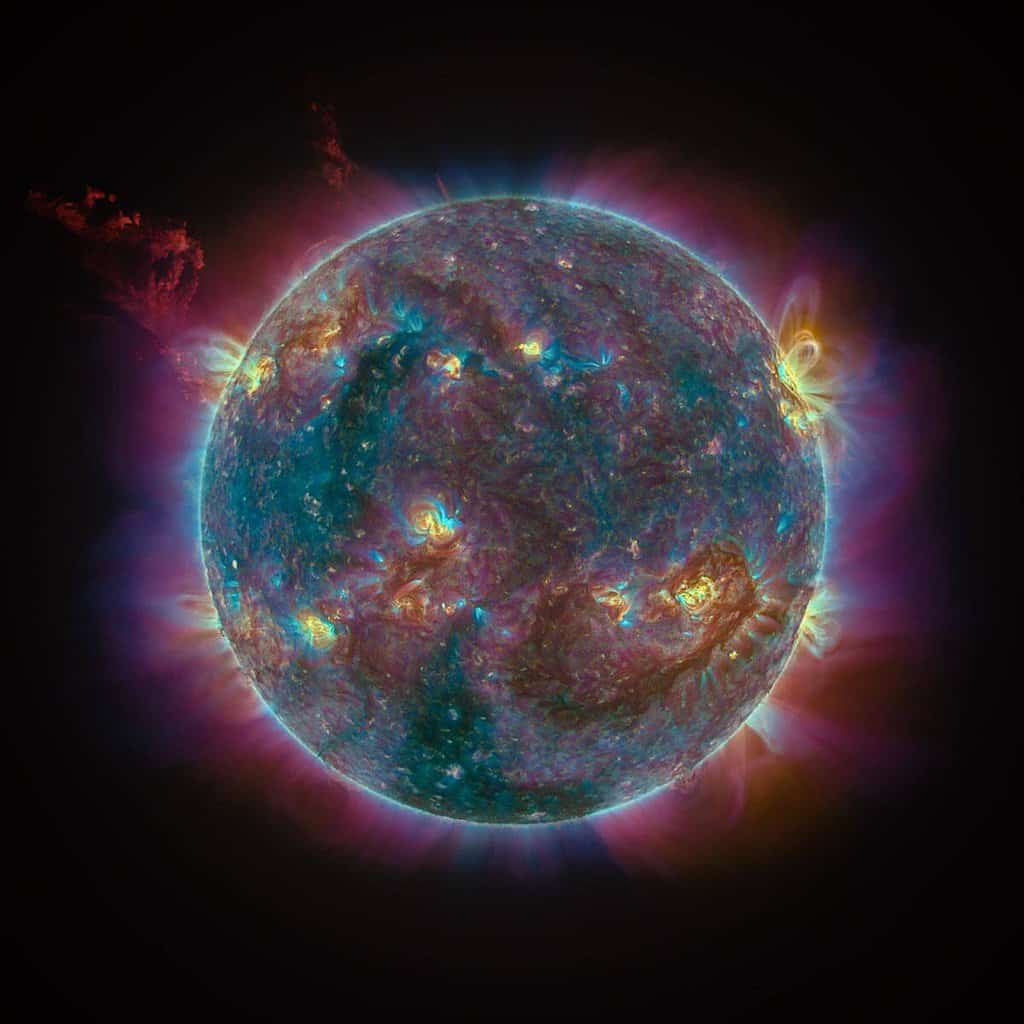

“Astrophotography is not only about capture, but also image processing, and that can actually become the most important part of it. This is especially the case with deep-sky astrophotography, where we build the image through processing without having a visual reference”

Why Astrophotography Using Public Data?

When we approach astrophotography for the first time, we tend to think of it in terms of photographic capture: we get the best equipment we can afford, spend some time wrangling it, plan our sessions under dark skies, taking as many shots as we can, etc.

As an amateur photographer, naturally I also went along this path myself. But astrophotography is not only about capture, but also image processing, and that can actually become the most important part of it.

For me, this is especially the case with deep-sky astrophotography, where we actually build the image through processing without having a visual reference.

As astrophotographers, we interpret our data through image processing to build a visualisation that balances the information in a communicative, aesthetic way.

If we give this due credit to image processing and recognise the value of this data visualisation approach as a creative, artistic process, then it should not be surprising that existing, public data may also be a perfectly valid raw material for our work. It is our personal, unique interpretation that provides life to this data.

Where Do You Get the Data?

There are many sources for public data, but probably one of the most amiable for the amateur is the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) Portal hosted by the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI).

With the advanced search option, you can easily narrow down by mission, instrument, and filter, list possible targets, and preview images before downloading them.

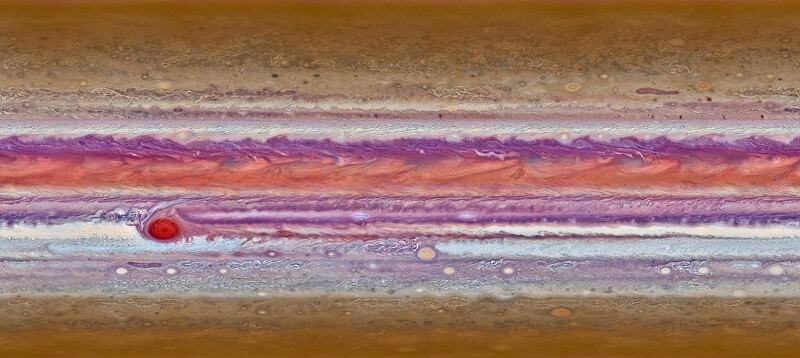

Other sources include ESA Sky and ESO Science Portal, both based on the user-friendly Aladdin Lite Virtual Observatory viewer, and the Junocam website, to name a few.

Some amateurs also give away their data in social networks or their personal websites, e.g. Wei-Hao Wan (who is also a professional astronomer).

Remote observatories that offer subscription of pay-per-use services are becoming popular among advanced amateurs (something that speaks in favor of the importance of the image processing itself) and some of them share sample master files that we can use.

In any case, we must ensure proper credit to our data sources.

What Programs and Processes Do You Use To Produce Your Images?

I use PixInsight for almost all the processing steps, with a few exceptions.

For example, if I have to compose layers or manually clean some distracting artifact, I use Adobe Photoshop.

When I have to blend multiple bands, a situation typical with professional data, I usually rely on a little command-line tool named dimred that I developed a few years ago.

It implements a Principal Components Analysis projection to the CIELAB or Oklab colour spaces.

I have no fixed workflow, but I have a ‘common thread’ in mind and try to adapt according to what I believe every image needs.

How About Your Own Image Capture?

The capture process creates an opportunity to tinker with the many technical challenges that naturally arise, something that as an engineer I usually enjoy.

Well, sometimes they are not exactly fun, but they push us to learn new things!

I live in a mid-sized city in southern Spain, Seville, that suffers from severe light pollution.

My rooftop is private, so I try to image from home whenever weather permits.

It is far from ideal, but it is what I have at hand, so armed with narrowband filters and patience I have made quite a few deep-sky images that probably would require far less integration time if I had captured them in the countryside.

In cities like mine, with ongoing migration to LED, narrowband filters are becoming less usable, especially the OIII band.

On vacation, at least once in a year, I travel to dark skies and spend some days there with my family.

Planning for those nights can be a bit overwhelming because I try to squeeze every minute, but having the main imaging equipment automated definitely helps (when it works as expected, that is).

That frees me some time to prime a lighter setup based on a Canon EOS 6D astro-modified camera and an Astrotrac TT320X-AG star tracker, and then relax while observing visually.

For this camera, I always apply 1x drizzle integration in PixInsight, which helps a lot in terms of compensating the loss of spatial resolution of the Bayer matrix.

The lenses I mainly use are the:

- Samyang 24mm F1.4

- Sigma 50mm F1.4 Art

- Samyang 135mm F2

As main imaging equipment, I use:

- Skywatcher AZ-EQ6 Pro mount

- Tecnosky 90mm F6 FPL55 APO and 0.8x dedicated reducer/flattener

- Omegon veTec 571C OSC camera

- Custom-made electronic focuser

- Intel NUC computer coupled to the mount

- Guiding is done with a no-brand 60mm F4 scope and a ZWO ASI120MM-S camera

The OSC, CMOS-based camera was a recent addition to upgrade a reliable Moravian Instruments G2-8300FW CCD camera.

It may seem strange to leave the monochromatic process behind, but I feel this is the right choice for me these days, both financially and in terms of enjoyment, given that I do not spend as much time imaging as I would like.

To image under polluted skies, I install an Optolong L-Ultimate filter and extend the exposures accordingly.

“Stay true to what awakens your curiosity and enjoy the path of learning it. There is no need to take shortcuts if the path itself is fun. Use tools where they can provide productivity, but do not let them intrude on your creative, artistic process.”

Can You Recommend Any Learning Resources For Other Astrophotographers?

We astrophotographers tend to focus too much on the technical side of things, and that is why I would recommend in the first place a more profound, even philosophical book about this subject: Fotografiar lo invisible by Vicent Peris (2020).

This book will definitely help you think about your work and see astrophotography from another perspective. For now, it is only available in Spanish, but translation to English is on its way.

Regarding image processing, there are many resources online, especially video tutorials, so it may be very difficult for a newcomer to discern good material. I would recommend building a solid foundation by studying the official learning resources from the PixInsight YouTube channel developed by the WeDoArt team.

From there you will be in the position of following the processing examples in the official PixInsight site, experimenting by yourself, and watching other tutorial sources with good judgement about whether that workflow meets your standards or not.

The book Inside PixInsight by Warren A. Keller can be of help when the otherwise excellent official PixInsight reference documentation is not yet available.

Regarding image capture, my favourite book is Astrophotography by Thierry Legault, whom I think of as the Cartier-Bresson of astrophotography. Published back in 2014, a new, updated edition would be desirable, but its core contents are very solid and make this book a must read.

A bit of advice, or warning if you like, that applies to both ‘classic’ photography and now also to astrophotography: There are a growing number of sources that lead to an oversimplification of image processing:

- Tutorials with recipes for fast results

- Big-button tools powered by AI that produce or help to produce automatically eye-catching images tuned for ‘likes’ on social networks.

These tools themselves are, in many cases, respectable, complex pieces of software, and I do not intend to discredit them. But you must decide what your role in all this is: If you blindly follow a recipe and produce results hitting a button, then maybe you are a consumer more than a producer, part of an audience instead of an author.

Stay true to what awakens your curiosity and enjoy the path of learning it. There is no need to take shortcuts if the path itself is fun. Use tools where they can provide productivity, but do not let them intrude on your creative, artistic process.

About You – Sergio Díaz Ruiz

Probably as many of you, I have been an astronomy enthusiast since childhood.

I had a couple of illustrated books from the collection ‘The Young Scientist’: ‘Stars & Planets’ and ‘Spaceflight’, that captured my young imagination. Watching ‘Cosmos’ by Carl Sagan was the definitive bump.

The work of David Malin and Akira Fujii started my interest in astrophotography, but I had to wait until my 20’s when I could afford a camera.

In 2020 I developed interest in public data and began to produce my first images with them.

I’m a member of the Astronomía Sevilla Association, the Andalusian Network of Astronomy (Red Andaluza de Astronomía, RAdA) and the Federation of Astronomical Associations of Spain (Federación de Asociaciones Astronómicas de España, FAAE).

I have an MSc in Computer Engineering and a few years ago I reinvented myself as a data scientist, something that naturally influenced my perspective about astrophotography.

In the last three years, I made myself enter some competitions mostly because it is a way to compel me to work on an image or an idea under a fixed deadline. I didn’t think it would go so well!

You can get to know me a little more on sergiodiaz.eu, and you can reach me by Astrobin, Mastodon and Twitter.

The featured image at the top of the article is entitled Busy Star, and was shortlisted in the Image Innovation category of the Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition 2022. [NOAA/NCEI SUVI Team, Image Processing by Sergio Diaz, 2022].

See more Skies & Scopes interviews and case studies like this here.